In May 1940 Germany invaded France. British troops in France retreated to the channel coast and most of the British Army was evacuated from Dunkirk but left most of their equipment behind. France quickly surrendered and there was a real danger that Britain would be the next target for invasion. General Ironside was given the responsibility of organising Britain’s defences. The first line of defence was along the coast but further inland a series of stop lines was envisaged that could halt the German advance if they broke through the coastal defences. These stop lines consisted of natural barriers and constructed defences. One stop line ran along the Thames upstream from London and along the Avon upstream from Bristol. Unfortunately, there is a gap between the two rivers and this gap was plugged by a defensive line (GHQ stop line red) running from Great Somerford on the Avon to Lechlade on the Thames, then further on to Tilehurst near Reading. Part of this gap was defended by an anti-tank ditch and pillboxes. The anti-tank ditch ran from just north of Wootton Bassett to the River Ray at Mouldon Hill in Swindon. Additional defensive support was provided by seven pillboxes along the route with an additional pillbox situated just north of Blunsden station.

Fig 1 Pillbox, north of Lydiard Millicent, west of Manor Hill Farm

Fortunately, the defensive line was never tested and after the war the ditch was filled in. Of course, the material from the ditch didn’t go back in completely and there was a hump where the ditch had been. Most landowners waited for the hump to settle but some spread the hump out to make the ground flat. The hump can still be seen in many places along the route but in some places the line of the ditch is marked by a slight dip where the hump was bulldozed and settling occurred afterwards. Pillboxes had been constructed to withstand direct hits from tanks so were extremely difficult to demolish, so most were simply left alone.

The route has been studied before and around 2000 two complementary articles were published, one in the Lydiard 2000 magazine by Michael Saunders and one in the Purton Historical Society by Eric Tull. The article by Eric Tull had a map of the route. I wanted to see if there are still any visible remains of the ditch today (2023). Before starting out in the field I examined LIDAR images of the area. LIDAR provides an accurate image of the ground surface by surveying from a light aeroplane. The big advantage of LIDAR is that an image can be produced of the ground surface without vegetation so that it often reveals features that are not visible to the naked eye. LIDAR images are readily available from lidarfinder.com but I used images that used DEFRA data downloaded to ArcGIS. DEFRA is a government agency that originally used LIDAR data to assess flood risks but is now available for most of the country. ArcGIS is a software package for processing and displaying geographical information.

Some sections of the ditch show very clearly on LIDAR

Fig 2 In this LIDAR image the ditch starts in the bottom left hand corner and heads north-east, crossing the Flaxlands road, going through the stable yard before skirting Frith’s copse.

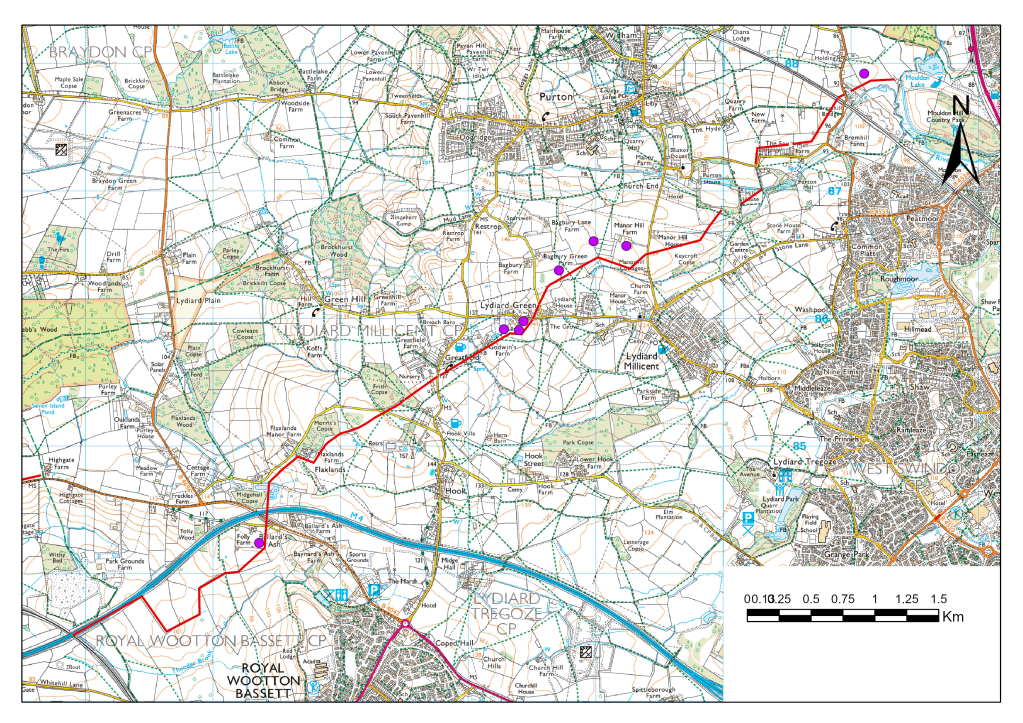

From the LIDAR images I was able to construct these maps of the route:

Fig 3 Route of the ditch from LIDAR images (Southern section)

Figs 4 Route of the ditch seen by LIDAR (Northern section)

However, there were some areas where the route of the ditch wasn’t clear. But another source of data has recently become readily available. The National Library of Scotland publish several different versions of Ordnance Survey maps on their website, maps.nls.uk , not just for Scotland but for the whole of the UK. Recently that have also published aerial photographs, joined together to form a continuous picture. Currently they cover mainly the south east of England. The aerial photographs were mainly taken just after WW2 when the RAF had surplus planes and surplus pilots. For the area we are interested in the photographs appear to have been taken after the ditch was filled in but it is still very visible.

Fig 5. Aerial photograph from the post-war period. The ditch showing in the area north of Lydiard Millicent. Pillboxes show as white spots. In the top right hand corner the ditch touches the edge of the cricket ground

The aerial photographs can now be used to complete the map of the route of the ditch.

Fig 6 Route of the Ditch (Red line) and position of pillboxes (Purple dots)

Update Oct 2023. Since I first published this blog more aerial photographs have been made available on the Historic England website and those taken by the USAF in 1943 have shown that, at the south west end of the ditch it continued to the railway line to about the same place as the M4 crosses it now. The M4 building work obliterated the last section of the ditch. The complete picture now looks like this:

So what can we see today? Obviously, the pillboxes are the most visible remains but there also remains where the ditch crossed a road. Rather than dig up the road, a roadblock was created using concrete blocks and after the war these blocks were simply pushed to the side of the road, where amazingly many still remain. These are near The Fox:

Fig 7 Concrete blocks used as anti-tank measures

And there are four on the ramp leading up to Bremhill Bridge:

Fig 8 One of the concrete blocks used as a roadblock on the approach to Bremhill Bridge

But, what of the ditch itself? This photograph was taken from Flaxlands Lane looking south and the hump of the ditch can be clearly seen in the foreground.

Fig 9. The hump of the filled in ditch near Flaxlands Lane

Other places where the hump can be clearly seen are at the bottom of Flaxlands Lane in the field below Flaxlands Farm where the line of the ditch runs parallel to the road, and in Mill House field between Stone Lane and Purton where the line of the ditch runs diagonally across the field.

The archaeological remains of GHQ Stop Line Red are an important reminder of the impact of WW2 on a quiet corner of North Wiltshire. There are other reminders and these will be explored in future Blog posts.

Keith Allsop March 2023

Further Reading:

Wills, H (1985) Pillboxes, A Study of UK Defences 1940. Leo Cooper/ Secker and Warburg, London

NLS Maps – this link takes you to the page where you can view the photographs https://maps.nls.uk/geo/find/#zoom=5.5&lat=55.20597&lon=-2.98946&layers=11&b=1&z=0&point=0,0

Historic England – this link takes you to the page where you can view photographs https://historicengland.org.uk/images-books/archive/collections/aerial-photos/