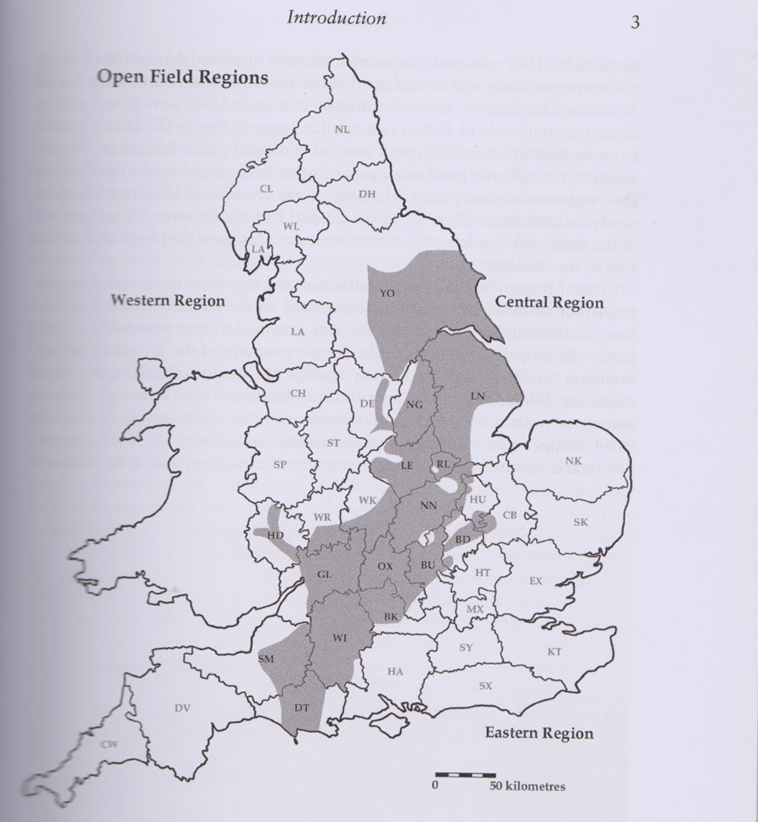

In the late Anglo-Saxon period there was an agricultural revolution in a belt through central England, running from Yorkshire to Dorset, starting around 850 (although some would date the changes later than this). The extent of the affected area is shaded in grey:

Map from ‘The Open Fields of England’ by David Hall

The most visible remains of this revolution are the fields of ridge and furrow but this was only one of several changes that happened at around the same time. One of the changes was the adoption of the mouldboard plough which enabled the creation of the ridges and furrows by using the plough to plough up one side of the ridge and down the other side, turning soil into the middle to create the ridge. These ridges and furrows were created in large open fields.

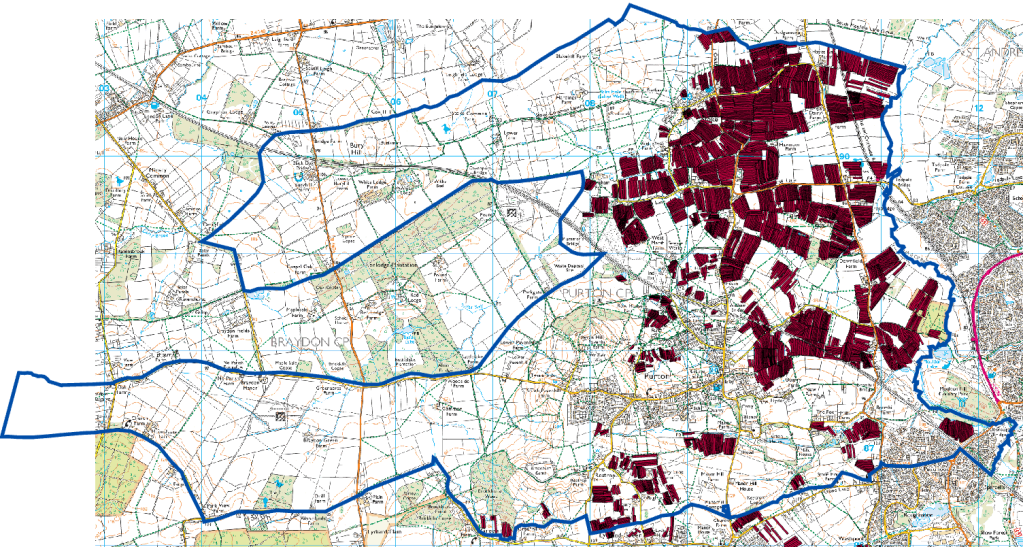

Ridge and Furrow near Watkins Corner, Purton

Originally each manor would have two or three open fields. In a two field system one field would lie fallow while the other grew a cereal crop, and the fields would rotate each year. If there were a third field this would probably grow peas or beans, rotating with cereals and lying fallow. Each strip of the ridge and furrow belonged to one household but there also some strips that belonged to the Lord of the Manor. The peasants would be required to work on the Lord’s holdings as well as their own strip.

The fields appear to have been managed co-operatively. All the householders grew the same crop at the same time; they planted at the same time, weeded at the same time and harvested at the same time. One of the other changes that happened at around this time was village nucleation. Prior to 850 the rural population was spread over the countryside in isolated farmsteads but after 850 villages tended to coalesce around the church and manor house. It is possible that this was a planned move so that all the villagers could more easily co-ordinate their efforts. However village nucleation was most noticable in the area described in the map and even then was not universal. Purton (Wiltshire) is an example of a settlement that remained dispersed. Carenza Lewis believed that the unusual settlement pattern was influenced by the proximity of Bradon Forest because other settlements around the Forest (Eg Lydiard Millicent, Brinkworth, Minety) also remained dispersed. I have used LIDAR to map the ridge and furrow of Purton in an effort to understand the development of the village. I traced a red line over the ridges shown by LIDAR, then removed the LIDAR layer for clarity and used the OS 1:25000 map as the base map. The map below shows the ridge and furrow in Purton parish using the modern parish boundaries shown as a blue line

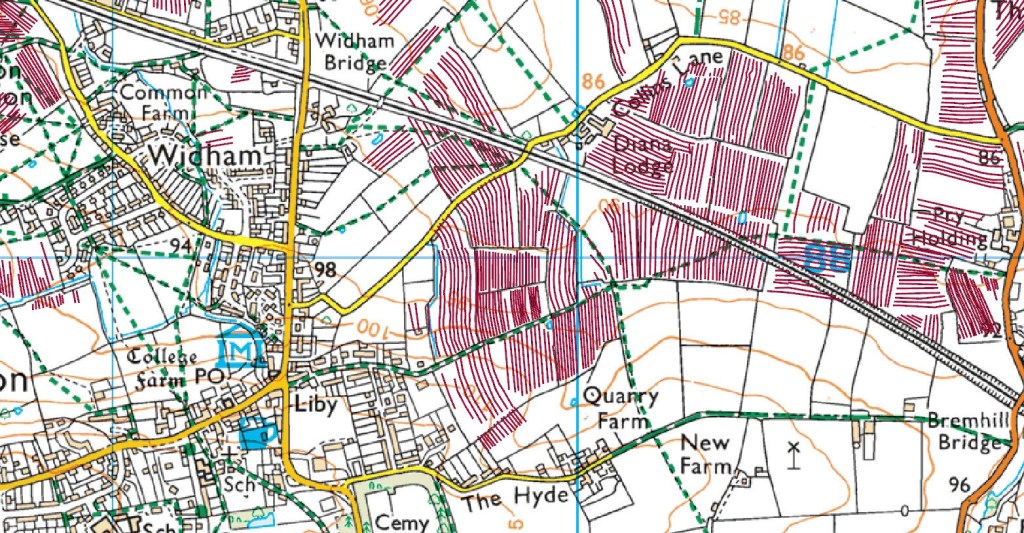

Purton is situated a few miles west of an expanding Swindon. It is a large village of approx 4000 inhabitants in a large parish. Most of the houses are spread out along the Cricklade Road to the north and the Malmesbury Road to the west. This route was part of the medieval Bristol to Oxford road, now known as the North Wessex Way. Roman remains have been found in the Dogridge and Pavenhill areas of Purton but the Romans in Purton project demonstrated that there was no continuity from Roman to Anglo-Saxon Purton. An Anglo-Saxon cemetery was found to the east of Purton near the area known as The Fox but there is no evidence for where the Anglo-Saxons lived. Most of the ridge and furrow that can be seen on the LIDAR images is concentrated to the north of the current village around the subsidiary settlement of Purton Stoke but there is some ridge and furrow closer to the main village. An example is shown in the map below:

The map shows that the ridge and furrow that starts near The Hyde was continuous to beyond the railway line. The furrows are about half a mile long and are the typical reverse S shape of early medieval ridge and furrow. The ridge and furrow was created by teams of 8 oxen pulling a mouldboard plough and at each end of the strips there would have been a headland that would be used for turning the oxen and not be ploughed. This headland can be seen at the northern end of the ridge and furrow, being ploughed at a later date when draught animals were larger and therefore fewer animals were required and the team became more manoeuvrable.

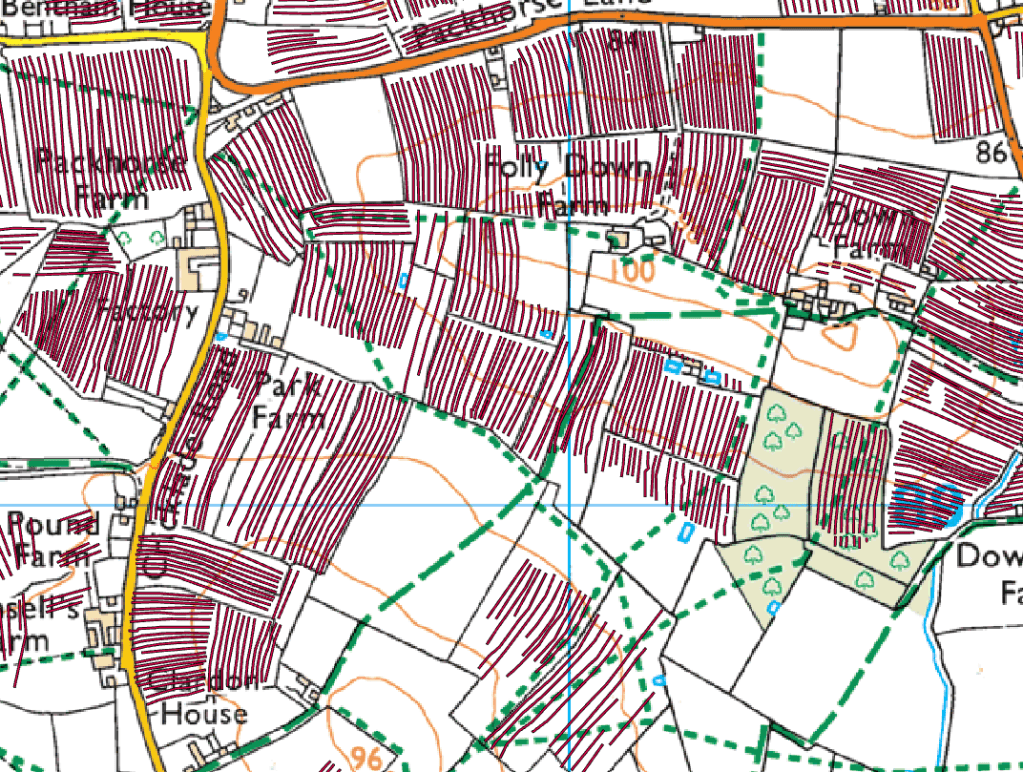

The ridge and furrow just to the north of this section has similar characteristics- long furrows and reverse S shape:

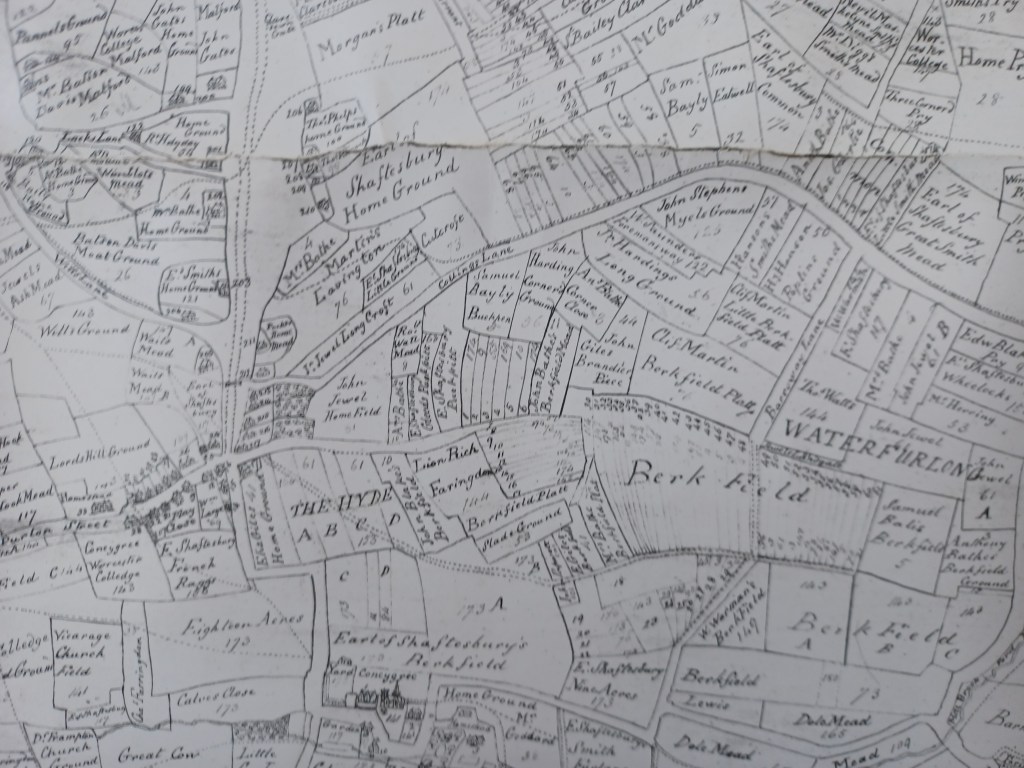

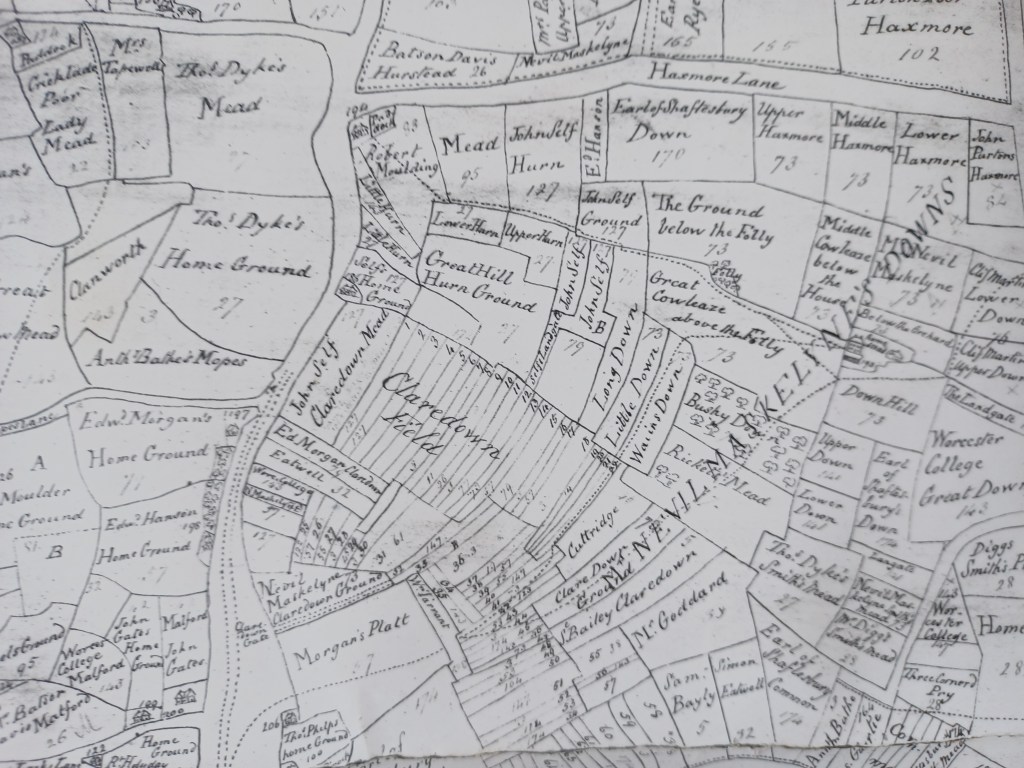

The fields of Purton Parish were mapped in 1744 after the 1738 Enclosure Act had been implemented. In this map the first field was known as Berkfield and the second one as Clardon (or Claredown) Field. These fields were probably the original fields of Purton’s pre conquest two field system, rotating between growing cereals and lying fallow. Early in the second millenium the climate got warmer and the population grew, so new ridge and furrow was created, mostly around Purton Stoke which was not known until 1257. This later ridge and furrow was generally shorter and straighter. It is estimated that, at the time of Domesday the population of England was around 2 million and by the start of the fourteenth century it had tripled to around 6 million. There were some severe weather events in the second decade of the fourteenth century that led to widespread starvation so it is likely that the population had passed its peak by 1348 when the Black Death had a devastating impact with one third to one half of the population being killed. This was not a one-off event; the Black Death was endemic for the next 100 years so the population did not recover for a long time. It is probable that most of the ridge and furrow we see today was created before 1315.

In 1744 the open fields had been part enclosed but parts of the fields were still being farmed in strips:

Final enclosure of the open fields didn’t happen until the end of the 18th century so this system of farming lasted around 1000 years. Amazingly there has been some survival into the present day. At Laxton in Nottinghamshire the cooperation between landholders still exists. Even though the farmers use modern equipment and strips have undergone some consolidation three open fields are still farmed by the landowners working co-operatively and village is now an important heritage site.

Farming in the parish of Purton is now almost exclusively devoted to animals, mostly cattle, either for dairying or beef. The fields are only growing grass, either for pasture or for haymaking and/or silage. The ridge and furrow is a reminder that arable agriculture was once a vitally important part of the local economy, vital to the survival of the local population.

Why Ridge and Furrow?

From the introduction of farming in the Neolithic period to the 17th century the rural population of England got most of their calories from the cereals that they grew. They were always one crop failure away from starvation. It has been suggested that the creation of ridge and furrow was a way of getting consistent output. If both the ridge and the furrow were planted with seed, if there was a dry summer the crop on the ridge would not grow so well but the furrow would retain some moisture and grow a reasonable crop. If there was a wet summer the furrow would be waterlogged and not have a good crop but the ridge would be better drained and still produce food for the table.

The other possibility is that ridge and furrow enabled autumn planting which improved yields. The danger with autumn planting is that the ground becomes waterlogged in winter and the seed rots in the ground. If the seed was planted only on the ridges which are better drained autumn planting would then become possible. No seed would be wasted and yields would improve.

Notes

I have dated the formation of the open fields to around 850. This is based upon information in the English Heritage book, England’s Landscape – The East Midlands by David Stocker, p59-65. Analysis of pottery finds in the open fields of Leicestershire and Northamptonshire demonstrated that, before the mid 9th century dense scatters of pottery indicated the presence of former settlements. After the mid 9th century the pottery was scattered thinly across the fields indicating domestic waste was being used to manure the fields. Modern villages have significantly more pottery after the mid 9th century. The obvious drawback to this conclusion is that it may not apply to other areas and the open fields of Leicestershire and Northamptonshire may have been created in the mid 9th century but the open fields of Purton may have been formed at a different date.

A study of Whittlewood by Jones and Page, also published in 2006, looked at twelve parishes on the Northamptonshire/Buckinghamshire border and revealed a more complex picture. They also concluded that 850 was the key date. Some parishes had no medieval settlement prior to 850. Some parishes had settlement prior to 850 and some were abandoned around 850 but others developed slowly into later villages. The open fields of ridge and furrow were laid out after 850. This sequence of events seems more akin to the situation in Purton than the situation studied by Stocker.

There is some dispute about the first known date of Purton Stoke. ‘The Place Names of Wiltshire’ claims that it is the Stoche listed in Domesday but I can’t find an entry for Stoche in Wiltshire. Purton Stoke is first mentioned in 1257.

Further Reading

The best modern book on open fields is ‘The Open Fields of England’ by David Hall, 2014

For Anglo-Saxon farming in general read ‘Anglo-Saxon Farms and Farming’ by Debby Banham and Rosamond Faith, 2014

The North Wessex Way, the ancient route through Purton is described in the website: https://northwessexway.co.uk/

Jones, R. and Page, M. (2006) Medieval Villages in an English Landscape

Stocker, D (2006) England’s Landscape – The East Midlands

Acknowledgements

The maps of distribution of ridge and furrow in Purton were created in ArcGIS using the OS 1:25000 map as a basemap and downloading LIDAR data from the Environment Agency website. © Ordnance Survey

Judith Rouse has transcribed the 1738 Enclosure Act and her daughter Emma was responsible for the photography and creating the digital images of the 1744 map (Emma Rouse BA Hons, MA, MiFA). These digital images can be viewed on the Purton Museum website: https://www.purtonmuseumandhistoricalsociety.com/the-1744-enclosure-map